|

A tragedy by William Shakespeare. Opened at the

Royal Court

Theatre, London, April 21, 1921. Closed on June 18, 1921, after 68 performances.

Producer

and Director, J. B. Fagan; General Manager, A.W. Chappell; Stage Manager,

George Desmond; Assistant Stage Manager, John Collins; Costume Designer, Theodore Komisarjevsky;

Costumes for Miss Titheradge and Miss Grey, Madame Robert Brochet; Other costumes, B. J. Simmons & Co. Ltd. and Tom Heslewood;

Wigs, Clarkson; Scenery construction, H. E. Hutton; Scenery painter, R. D'Amar;

Lighting and set designer, J. B. Fagan; Lighting carried out

by Charles Hammond; Electric lighting by Alfred Walters; Music under the direction of J. H. Squire;

Fights arranged by Felix Grave.

|

Cast of Characters

|

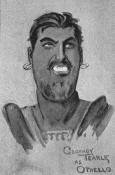

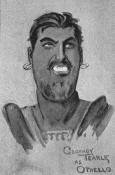

Othello |

Godfrey Tearle |

|

Iago |

Basil Rathbone |

|

Cassio |

Frank Cellier |

|

Montano |

Eugene Leahy /

Aubrey Fitzmaurice |

|

Lodovico |

C. Thomas |

|

Duke of Venice |

John Collins |

|

Brabantio |

Alfred Clark |

|

Roderigo |

Eric Cowley |

|

Gratiano |

Aubrey Fitzmaurice |

|

Desdemona |

Madge Titheradge /

Moyna Macgill |

|

Bianca |

Gwendolen Evans |

|

Emilia |

Mary Grey |

| |

|

|

| |

|

| As written by William Shakespeare, Othello is a five-act play,

but Mr. Fagan has arranged the tragedy in three acts of ten scenes. The five scenes of

the new first act take in the whole of the first two acts of

Shakespeare's original. The new second act corresponds to the original third

act plus the first scene of the original fourth act. Mr. Fagan's third act is made up of the rest of Shakespeare's fourth and fifth acts.

|

|

| ACT I |

Scene 1: A Street in Venice.

Scene 2: The Sagittary.

Scene 3: A Council Chamber.

Scene 4: A Corridor.

Scene 5: A Seaport in Cyprus. |

| ACT II |

Scene: A Loggia in the

Castle. |

| ACT III |

Scene 1: A Room in the Castle.

Scene 2: A Bedchamber.

Scene 3: A Street.

Scene 4: A Bedchamber. |

|

|

The playbill |

|

The play opens on a street in Venice. Here we are introduced to Iago, a soldier, and Roderigo, a rich man who is in love with Desdemona,

daughter of a senator in Venice. Iago and Roderigo are

complaining about Othello, a Moor and general of the Venetian army. Both of

them hate Othello—Roderigo because

Othello has secretly married Desdemona, and

Iago because he believes Othello passed him over for a promotion in

favor of a young, inexperienced soldier named Cassio. Iago begins plotting

vengeance against Othello. The play opens on a street in Venice. Here we are introduced to Iago, a soldier, and Roderigo, a rich man who is in love with Desdemona,

daughter of a senator in Venice. Iago and Roderigo are

complaining about Othello, a Moor and general of the Venetian army. Both of

them hate Othello—Roderigo because

Othello has secretly married Desdemona, and

Iago because he believes Othello passed him over for a promotion in

favor of a young, inexperienced soldier named Cassio. Iago begins plotting

vengeance against Othello.

Iago and Roderigo hasten to inform Brabantio, the

girl's father, of her elopement with Othello. Brabantio is horrified, but before

he can confront Othello, he is summoned to an urgent

meeting of the Senate regarding the imminent threat of a Turkish invasion fleet on

the Venetian-held island of Cyprus.

Othello is already at the council because he has been put in command of the

forces to repel the Turks.

Brabantio interrupts the

meeting to accuse Othello of winning Desdemona

by witchcraft. Defending himself, Othello tells how he won her love by

telling her of his great adventures. Desdemona agrees and swears that she married

Othello for love. Brabantio interrupts the

meeting to accuse Othello of winning Desdemona

by witchcraft. Defending himself, Othello tells how he won her love by

telling her of his great adventures. Desdemona agrees and swears that she married

Othello for love.

Because of the Turkish threat,

Othello departs immediately for Cyprus to defend the island against the Turks. He leaves Desdemona behind

with Iago, promising that she shall come to his camp as soon as it is safely established on the island of

Cyprus.

No sooner has Othello landed than he learns that a tempest dispersed

the Turkish fleet and thus the island is free from any immediate threat of

an attack. When Othello is reunited with Desdemona on the island, he announces that

there will be feasting and gaiety that evening to celebrate Cyprus’s safety

from the Turks. Iago plans to use young Cassio to arouse Othello's jealousy, but

first he will lower Cassio in the esteem of his general.

That night Othello puts Cassio in charge of preventing the soldiers from drinking

in excess so that no

brawl might take place. The wicked Iago leads the young soldier to drink a

little bit too freely, under the pretense of honoring their general. During the feast Iago manages to involve Cassio in a quarrel with Roderigo.

In an attempt to break up the scuffle, the governor of Cyprus is wounded. A

riot ensues and Iago has the alarm bell rung. When Othello comes upon the scene he orders Cassio deprived of his commission in

the army.

The next day, Iago urges Cassio to ask Desdemona to intercede for him as

Othello could not refuse her anything. Cassio, unsuspicious of what Iago is

attempting, takes his advice and pleads with Desdemona to have him

reinstated. Desdemona reassures him that she will speak to Othello on his

behalf.

Hastening to Othello, Iago hints that there is an affair of some

sort between Desdemona and Cassio. The Moor will not believe his wife

is false to him, and yet is much hurt when she urges him to restore Cassio to his

rank of chief lieutenant.

Still

doubting, Othello demands proof that his wife is unfaithful. Iago asks

Othello if Desdemona owns a handkerchief embroidered in strawberries.

Othello answers in the affirmative, adding that he himself gave her such a

handkerchief; it was his first gift to the woman he loved. Iago then

explains to the unhappy husband that he has seen this very

strawberry-spotted handkerchief in the possession of Cassio. (Actually,

Iago's wife Emilia found the handkerchief that Desdemona had dropped and

passed it to Iago, who planted it in Cassio’s room as

“evidence” of Cassio’s affair with Desdemona.) Iago suggests that Desdemona has given Cassio

the handkerchief. Furious, Othello threatens to kill Cassio. Still

doubting, Othello demands proof that his wife is unfaithful. Iago asks

Othello if Desdemona owns a handkerchief embroidered in strawberries.

Othello answers in the affirmative, adding that he himself gave her such a

handkerchief; it was his first gift to the woman he loved. Iago then

explains to the unhappy husband that he has seen this very

strawberry-spotted handkerchief in the possession of Cassio. (Actually,

Iago's wife Emilia found the handkerchief that Desdemona had dropped and

passed it to Iago, who planted it in Cassio’s room as

“evidence” of Cassio’s affair with Desdemona.) Iago suggests that Desdemona has given Cassio

the handkerchief. Furious, Othello threatens to kill Cassio.

Just to be certain, Othello asks Desdemona for her handkerchief and when

she cannot not find it, Othello's worst suspicions are confirmed. With angry

words he bursts from the room in a jealous rage. Othello orders Iago to kill Cassio and

plans to kill Desdemona himself. When wife and husband meet

again he accuses the woman more plainly of unfaithfulness. Surprised and

terrified at the change that has come over her once loving husband,

Desdemona retires weeping to her room.

Later, as Desdemona sleeps, Othello enters, and going over to her, kisses her

forehead. Awakening, Desdemona raises herself on her arm

and with tears in her eyes tries to clear herself of the accusations he has

brought against her. But he refuses to listen to her pleadings and smothers

her with a pillow.

Emilia, wife of Iago, enters and is horrified by the sight of Desdemona's body. Othello

tells Emilia that he killed Desdemona for her infidelity, citing

the handkerchief as proof. Emilia defends Desdemona’s innocence, and says that Iago lied. She explains how Desdemona's handkerchief came into Cassio's

possession. Reacting to his wife's accusations, Iago stabs and kills Emilia.

Othello realizes that Iago is

behind the tragedy and

tries to kill him.

Just at this

moment Cassio is brought into the house wounded and bleeding, as Iago had sent

Roderigo to assassinate him. The attempt,

however, was not successful and Cassio is not mortally wounded. Letters are

revealed that make the treachery of Iago and the innocence of Cassio clear

beyond a doubt. This blow is too much for the Moor, who, realizing the limits to which his blind passion has

carried him, stabs himself and dies at the feet of his dead wife. Just at this

moment Cassio is brought into the house wounded and bleeding, as Iago had sent

Roderigo to assassinate him. The attempt,

however, was not successful and Cassio is not mortally wounded. Letters are

revealed that make the treachery of Iago and the innocence of Cassio clear

beyond a doubt. This blow is too much for the Moor, who, realizing the limits to which his blind passion has

carried him, stabs himself and dies at the feet of his dead wife.

The story ends with Cassio becoming

governor of Cyprus and sentencing Iago to a lingering torture.

(The plot summary above is embellished with drawings from The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News,

May 21, 1921.)

|

TRAGEDIAN TEARLE "ARRIVES."

Godfrey Tearle's Othello at the Court

was better than I expected—and I expected a lot. I knew that he is no tyro in

Shakespearian art. I had seen his father Osmond and his uncle Edmund many a

time, and I was aware of Godfrey's early and arduous training in their

Shakespearian traditions. His recent successes in London had familiarised me

with his strong personality and histrionic accomplishments. Yet his Othello

surprised me. It was first and foremost an elocutionary triumph. Only

Forbes-Robertson spoke the poetry of the part more beautifully. Forbes-Robertson

in other respects was not a great Othello; and Godfrey Tearle, in some of those

respects—notably the fire and agony of the character—was as good as any Othello

I have seen, with the single exception of Grasso's.

And I have seen a good many Othellos—even

H. J. Nettlefold's!

Therefore, if you are a conscientious

playgoer, you must go to the Court to see this splendid embodiment of the noble

Moor. Next in importance in Fagan's fine revival of the tragedy is Basil Rathbone's Iago. It is a good Iago—the right age (twenty-eight), but a shade

modern and meticulous. Rathbone, like Tearle, speaks the poetry musically. Madge

Titheradge's Desdemona slightly disappointed me. I liked her tenderness and

sweetness, but her tone is not Shakespearian. Frank Cellier was immense in

Cassio's "drunk" scene, but he is a pocket Cassio to look at. The Emilia of Mary

Grey didn't get there at all. There is an actress named Ethel Griffies who can

make you jump out of your seat as Emilia.

Fagan's production of "Othello"

achieves wonders on his tiny stage. It is artistic, full of colour, and

ingenious in obtaining effects of height and space. In this last respect the

Council Chamber scene is something to marvel at. Once again, bravo, Fagan!

—The Sporting Times, April 30, 1921 |

Othello premiered at

the Royal Court Theatre during William Shakespeare's birthday week. (Mr.

Shakespeare would have been 357 years old in 1921.) Opening night was attended by

a number of celebrities, including Lloyd George, Lord Balfour, Anthony Eden and Lady Colefax.

As Rathbone recalled, the

play seemed to be going well, but then he developed an uncontrollable case

of the hiccups during the second half of the performance. Though afraid that

the audience would laugh at him, Rathbone made his entrance onstage and

hiccupped through a scene with Desdemona. He wrote, "No laughs ... warm

applause greeted my exit. On the following morning I received excellent

reviews from the press. One leading London newspaper picked out, in

particular, the scene with Desdemona I have just mentioned. For this scene I

received special praise for my brilliant conception in playing Iago, drunk!"

(In and Out of Character, p. 47)

In an interview, Rathbone

stated that playing Iago was a great experience. He added, "We can all understand Iago’s motives in ‘Othello,’ even though we loathe

him, because he appeals to the intelligence."

(“He Resents Being Typed,” Silver

Screen,

July 1936)

The character of Othello was played by Godfrey Tearle, son of acclaimed

Shakespearean actor/manager Osmond Tearle. Basil Rathbone wrote that Godfrey Tearle was the best Othello that he had ever seen.

Six members of the Othello cast had appeared with Basil Rathbone

in King Henry IV, Part II, February 17 to April 16, 1921: Frank

Cellier, Alfred Clark, C. Thomas, Eugene Leahy, John Collins, and Mary Grey

(a.k.a. Mrs. J. B. Fagan).

Godfrey Tearle, Madge Titheradge, Mary Grey, Basil Rathbone

(photos from the playbill) |

Gwendolen Evans, Eugene Leahy, Alfred Clark, Frank Cellier, John

Collins, Eric Cowley

(photos from the playbill) |

Most critics praised Rathbone's performance as Iago. A few, however, felt that Rathbone wasn't convincing as a villain.

(Ironic, since Rathbone was later typecast as a villain!)

"I did not

think Mr. Basil Rathbone altogether successful in rendering plausible to us so

much cold-blooded villainy. Much as I admired the lightness and precision of his

playing, I began to doubt before the end whether he had started with any

very clear conception of the character." —Truth, April 27, 1921

"Mr. Rathbone is

always making the audience laugh with the pungency of Iago’s wit; as he

strolls through the play with his lithe, graceful movements, you miss the

cigarette between his fingers. He is critical, peevish, spiteful—anything

you like, but not dangerous. Gradually the conviction gains on you that here

is an Iago who would hamstring no Lieutenants, bring about no murders. ... Rathbone gives

us a delicate study, a cleverly executed study, but not for a moment the

Colossus needed to sustain this mighty tragedy." —D. L. M.,

The Nation and the Athenaeum, May 7, 1921

While some critics were not convinced of Iago's villainy, Rathbone's

girlfriend at the time, a woman he called Kitten, found his performance

frightening. He recalled that she said, "How can you play a part like that, and not be something

like it yourself? ... You frighten me."

(In and Out of Character, p. 47)

Other critics, such as this one for The Scotsman, felt that

Rathbone hit the right note with his interpretation of Iago:

"Mr. Basil Rathbone realized the utter, almost detached,

scoundrelism of Iago, his deliberate villainy, be he perhaps made the character

too brutal and not intellectual enough. But that is a refinement of criticism

which could only be brought against a convincing performance." —The Scotsman, April

22, 1921

|

FINE ACTING IN THE COURT THEATRE

REVIVAL

One sometimes wishes that Shakespeare

had written more about ordinary people, and less about Kings; and it is perhaps

half the secret of the popularity of "Othello" that it is the domestic tragedy

of simple, comparatively ordinary people, people "of like passions" with

ourselves and caught in the toils of a particular passion which we see daily at

work. The play probes the human sympathies as none other of the tragedies can do.

Given an Iago, we feel that it might have happened to us.

With an actor like Mr. Godfrey Tearle

in the part of the Moor, the illusion becomes terribly real. Last night at The

Court he gave a great performance. His range of expression was remarkable. He

was exactly the rude and powerful soldier, and, if anything, as the simple lover

of the opening scenes he was too smooth and lovable to be the cruel and violent

creature of the later ones. the crescendo of jealousy was made extraordinarily

real, so real that its steepness was forgotten. All through he lived the part to

an unusual degree, and his despairing cry to the the dead Desdemona was

unforgettably moving. If the performance had a blemish, it was that he buried

the poetry of one or two passages in a too rapid emotional delivery, though

there were many which he spoke very beautifully, notably the speech in the

Council chamber and the "Farewell the tranquil mind."

Mr. Basil Rathbone's slim and

subtle Iago made an excellent contrast. This was an extremely clever and

thorough piece of acting, obviously the result of much thought and hard work. He

did look twenty-eight, and he did make us believe in his deliberate wickedness;

and if one scarcely felt that so impressive a person as Mr. Tearle's Othello

would have been deceived by it, that was not his fault. He did the difficult

soliloquies very easily and well, and it was a pity that one of them was spoiled

by a huge noise "off." The passages between these two in the second act were

magnificent.

Miss Madge Titheradge scarcely

reached the same level, but Desdemona has fewer opportunities. She was a very

gentle, quiet, and (except for the wig) beautiful Desdemona, and suggested the

naive bewilderment of the final scenes with touching effect; but even her best

moments suffered from a certain immobility of expression.

Mr. Frank Cellier's Cassio was a

deservedly popular performance, especially (I am afraid) the drunken scene, done

with much delicacy. Mr. Eric Cowley was not my idea of Roderigo, being too much

of a clown to have dreamed of aspiring to the favours of a Desdemona.

As to the production, one might have

heard a little more poetry; there were some taking pieces of staging,

particularly, perhaps, the simple hangings of the council Chamber; but the

lighting was often bad, especially in the Seaport scene, even supposing it had

proceeded according to plan; what with the recalcitrant stairs, the green-cheese

moonlight, the lamp which refused to light, charm the lamplighter never so

wisely, the heavy shadow of the lamp-post on the sky, and other imperfections,

the lighting department must look to't. Nobody minded, but there were so many

little hitches that if the acting had been of a less high order serious havoc

might have been caused. Little mechanical hitches can make the greatest actors

look silly, and that is a shame.

But the production deserves and, I

hope, will have, a great success.

A. P. H.

—The Westminster Gazette, April 22,

1921 |

Edwin Radford, with

The Nottingham Journal, criticized producer J. B. Fagan for

perverting

Shakespeare's play. Radford wrote, "He gives us in Mr. Godfrey Tearle and Mr. Basil Rathbone an

Othello and Iago who set us wondering which is the younger and the more

handsome. Othello became a fine-featured, olive-complexioned, irresistibly

attractive young Southerner, not a day older than thirty. Instead of

Desdemona being attracted by pity, we could hardly imagine her doing

otherwise than falling in love with this young god, in the natural way that

a young maid falls in love with a young man. Again, with Mr. Rathbone's

beautiful young Iago, 'villainous thoughts' could only be explained in one

so youthful and so fair by a theory of degeneration. This state of things

makes half the play meaningless."

(Nottingham Journal,

May 2, 1921)

The issue was Rathbone's age. Mr. Radford and a few other critics felt

that Iago should be played by an older actor, pointing out that Shakespeare

described Iago as a "bad old soldier."

Fagan countered this criticism by stating that in Shakespeare's Othello,

"Iago describes himself

in the first scene as being 28, and though he often tells lies, in this

instance it would be to his interest to exaggerate his age." (The Pall Mall Gazette, April 25, 1921)

Producer James Bernard Fagan, 1909

Photo by White Studio

|

Moyna Macgill, 1924

Photo by Bassano |

Many critics were disappointed in

Madge Titheradge's performance as

Desdemona. On June 2 she was replaced by Moyna Macgill, whose performance

pleased the critics.

"Miss Macgill is very intelligent. She subdued herself to Desdemona's rather tiresome

patience with a rather too visible skill; but when real acting was needed in the

dreadful moment after Othello's last worst outburst, just before the bedchamber

scene, she was wonderfully moving in her dazed and bewildered innocence. She

has, too, a grace denied to Mr. Basil Rathbone, whose handsome Iago was on far

too intimate terms with the audience. Miss Macgill plays into the play, not out

at the playhouse. She suggested a girl's mad infatuation throughout the early

scenes by the simple and entirely successful trick of never taking her eyes off

Othello if she could possibly help it, and even then only for the shortest

possible time. She is, in short, an artist." —The Westminster Gazette,

June 2, 1921

In 1925, Macgill became the mother of Angela Lansbury, who later acted with

Basil Rathbone in the 1956 film The Court Jester. Moyna

Macgill also appeared in Frenchman's Creek (1944) with Basil Rathbone; she played Lady Godolfin.

|

"OTHELLO" at the COURT THEATRE

Many people consider that Othello

is the best acting play that Shakespeare ever wrote, and nobody can doubt that

the play contains some of his noblest poetry. It is certainly the only play,

except perhaps The Tempest, in which unity of theme is observed, and here

the theme is so terrible, the unity so relentless, that we occasionally long to

have back some of the usual Shakespearean discursiveness at which we have

probably so often grumbled.

Mr. Fagan's production of the play is

on the whole a very satisfactory one. There are two intervals only, and though

the First and Third Acts, as he has arranged them, each contain a number of

scenes, the stage management is admirably competent, and one fades in as quickly

as the other fades out. even my rabid feelings about waits were soothed by such

excellent promptitude. All the scenes were quite pleasing; one in which the Doge

sits in Council in the Sagittary is really beautiful. Pink-purple curtains fall

in heavy folds, making the background of the stage. On a tall dais, about eight

steps high, sits the Doge in his gold brocade gown and cap; behind him falls

from his high canopy a broad panel of cloth of gold. this forms a very fine and

dignified setting for what is certainly one of the most admirably written scenes

in Shakespeare. Mr. Godfrey Tearle is a thoroughly competent actor, and made the

Moor most attractive, as a simple, honest, and almost childlike but at the same

time resolute man of action. I like the way in which Mr. Fagan shifts his

company about. Mr. Alfred Clark, who played Falstaff in Henry IV, was

acting the small part of Brabantio, and acting it exceedingly well. Mr. Basil

Rathbone was an admirable Iago. This sort of part seems to me to suit him better

than the "juvenile lead," when he is a little inclined to conform to the ideals

of the cinema hero. Iago is an almost impossible character to portray; it is

very difficult for an actor to make his motives appear sufficient. Another

good piece of casting was that of Miss Mary Grey as Emilia. She was excellent as

the slightly vulgar, slightly coarse-minded but affectionate, loud-mouthed

woman. Unfortunately, her costumes and those of Miss Madge Titheradge as

Desdemona are not a success. Mr. Tom Heslewood was responsible for the rest of

the clothes, and he is an expert on Venetian costume of the period chosen, but

on the programme we are told that Mr. Commisarjevsky was responsible for

Desdemona's and Emilia's dresses. In any case, somebody made a hash of it. Miss

Madge Titherage was handicapped by a most absurd voluminous tow wig, making her

look like a caricature of a stage ingenue. While the other two

women—Bianca and the waiting woman—were in well cut, coherent Venetian dresses,

she and Emilia wore a series of inchoate dressing gowns of colours which went

very ill with the scenery. Whether the fault was Mr. Commisarjevsky's or whether

it was a case of "leading lady" again, it is, of course, impossible to

determine. Mr. Eric Cowley acted pleasantly as Roderigo, a part obviously

written for Mr. Miles Malleson. Miss Gwendolen Evans as the demi-mondaine

Bianca is quite attractive to look at, but is unfortunately, exceedingly correct

in her behaviour. we wish she would go to her namesake Miss Edith Evans to learn

how to play a Venetian courtesan.

Tarn.

—The Spectator, May 7, 1921 |

"Mr. Basil Rathbone's Iago is very intelligent, for he avoids

all the pitfalls of the part, which so readily lends itself to transpontine

villainy."

—The Graphic, April 30, 1921

"Mr. Basil Rathbone's Iago was also a notable performance. ... The

spite and devilish ingenuity of the character were clearly brought out. ...

The

effect of the actor's performance became more intense as it proceeded. It

was never a great Iago, but it was always vivid and convincing, with the

subtle Italianate touch."

—The Saturday Review, April 30, 1921

"Mr. Basil Rathbone's conception of Iago is most skilfully worked out,

but he gives us the impression that he failed to act up to his own

intentions. He could not quite attain the sinister note, but remains

malicious, and at times a most agreeable fellow. Nevertheless, it was a

clever, subtle impersonation, and heightens Mr. Rathbone's reputation."

—The Era, April 27, 1921

"Basil Rathbone, an artiste who is

surely rising to the highest rank in the profession, gave a wonderfully fine

reading of Iago, full of insight and intellectual power, and lacking only,

perhaps, in the suggestion of diablerie in the villain's composition."

—Western Mail, April 23, 1921

Royal Court Theatre in 1888

(photo is ©

www.arthurlloyd.co.uk,

used by permission.) |

Royal Court Theatre in 2020

(photo by kwh1050) |

|

The Royal Court Theatre is located on the east side of Sloane

Square in London.

News articles from 1920 reported that

Mr. Fagan intended to make the Royal Court Theatre a permanent home for Shakespeare.

In a puzzling move, Fagan stopped producing Shakespeare plays after this

1921 production of Othello. |

|